Nel febbraio 2016 la notizia della prima salita invernale del Nanga Parbat da parte di un team italo-spagnolo-pakistano conquistò in tutto il mondo le prime pagine delle cronache alpinistiche. Il Nanga Parbat, dopo 28 tentativi falliti, era rimasto insieme al K2 uno dei due Ottomila non ancora saliti in inverno. Questo articolo si occupa della straordinaria figura di Albert Frederick Mummery, il primo uomo sulla terra che, addirittura nel 1895, quindi oltre un secolo fa, tentò la prima salita di questa maestosa montagna con una incredibile spedizione leggera. Un concetto dovrebbe essere chiaro prima di iniziare a parlare di Albert Frederick Mummery (10 settembre 1855, Dover, UK - 24 agosto 1895, Nanga Parbat, Pakistan): come già sottolineato Mummery fu un vero precursore dell'alpinismo moderno, infatti il suo modello di alpinismo fu in grande anticipo se paragonato al suo tempo, la fine dell' Ottocento.

I suoi concetti di arrampicata del tutto all'avanguardia anticiparono veramente il Novecento. Non a caso Mummery è noto come "il padre dell'alpinismo moderno".

Fu un personaggio fortemente innovativo non solo per essere stato uno dei primi alpinisti a rompere con la vecchia tradizione "dell'alpinismo con guide" e a dimostrare che era possibile salire le montagne anche senza l’aiuto di professionisti, come fece ad esempio nel 1894 sullo Sperone della Brenva; fu anche un sorprendente precursore per il fatto che seppe ampliare enormemente i suoi orizzonti e impegnarsi assolutamente in anticipo sui tempi in direzione delle montagne più alte della terra come possibile nuovo e ambizioso obiettivo.

Principalmente famoso per essere stato il primo alpinista della storia a progettare e tentare di scalare un Ottomila, in realtà Mummery fu uno dei più grandi alpinisti di tutti i tempi: prima del Nanga Parbat aveva realizzato molte diverse impegnative salite sulle Alpi e aveva anche effettuato un paio di spedizioni nel Caucaso, nel 1888 e nel 1890, durante le quali scalò il Dykh-Tau 5198 m. Mummery viene anche ricordato per la sua etica cristallina, convinto sostenitore com'era del grande valore di un confronto onesto tra uomo e montagna. Fu tra i primi a sostenere la necessità di arrampicare senza mezzi artificiali, contando solo su ciò che egli stesso definì "mezzi leali". Scrisse infatti che "l'arte dell'alpinismo è di migliorare il talento per le alte vette con mezzi leali".

Dopo la morte del padre, Albert e il fratello William furono mandati in vacanza sulle Alpi. In quella circostanza nacque la passione per l'alpinismo, come più tardi Albert scrisse nel suo famoso libro "Le mie salite nelle Alpi e nel Caucaso": "le falesie di Via Mala e le nevi del Teodulo hanno suscitato in me una passione, che è cresciuta con i miei anni, e hanno indirizzato non poco la mia vita e il mio pensiero". La sua prima salita sulle Alpi risale al 1871, quando Mummery salì sul Cervino a soli quindici anni. La prima fase delle sue attività (1879-1890) avvenne in compagnia della grande guida alpina svizzera Alexander Burgener (1845-1910), autore di prime salite di numerose vette e di nuovi itinerari nelle Alpi occidentali. Insieme a lui Mummery compì la prima salita della Cresta di Zmutt sul Cervino nel 1879, oltre a quella dei Grands Charmoz e dell'Aiguille du Grépon (1881).

All'inizio della sua carriera alpinistica Mummery, insieme a Burgener, formò una fortissima cordata che realizzò diverse salite impegnative sulle Alpi, ma in seguito fu profondamente innovativo. Infatti, in anticipo sui tempi, ad iniziare dal 1892 fu uno dei primi alpinisti a salire le montagne senza guida. Alla fine dell'Ottocento le magnifiche vette di granito delle Aiguilles de Chamonix, sebbene esercitassero un fascino irresistibile, non erano state ancora prese in considerazione dagli scalatori dell'epoca, in quanto ritenute estremamente difficili.

Grandes Jorasses e Dente del Gigante (Ph S. Mazzani)

Grandes Jorasses e Dente del Gigante (Ph S. Mazzani)

Mummery e Burgener progettarono per la prima volta di salire queste guglie ritenute impossibili e riuscirono nel loro intento: Aiguille des Grands Charmoz (con Benedikt Venetz), Aiguille Verte lungo il versante Charpoua (senza ramponi) e pochi giorni dopo l'inviolato e stupefacente Grépon 3482 m, la scalata alpina che per la sua audacia e difficoltà rese famoso Mummery: fu considerata la più grande arrampicata su roccia mai realizzata fino ad allora. Mummery festeggiò in vetta con una bottiglia di champagne e anche questo particolare significativo rivela la sua personalità e la sua propensione a tagliare i legami con la precedente concezione drammatica dell'alpinismo. Mummery ripeté quest'ultima salita nel 1893, senza guide.

Tra il 1879 e il 1880 Mummery e Burgener realizzarono la prima salita della già tentata Cresta di Zmutt sul Cervino e il ripido canalone settentrionale del Leone. Ancora una volta sul Cervino, Mummery con Benedikt Venetz tentò anche l'inviolata cresta di Furggen, deviando solo nell'ultima parte sulla via Normale (cresta dell'Hörnli). L'episodio più significativo riguardante l'etica di Mummery avvenne nel 1880: Mummery e Burgener progettarono di scalare il Dente del Gigante, ancora in attesa di essere salito per la prima volta. La cordata iniziò l'ascensione ma arrestò il tentativo di fronte a una placca di granito troppo liscia per essere superata in arrampicata libera. In quella circostanza Mummery lasciò sul posto una bottiglia contenente un messaggio che diceva: "impossibile con mezzi leali". (Ndr: in effetti quel tratto venne superato due anni dopo dalle guide valdostane Jean-Joseph, Baptiste e Daniel Maquignaz forando la roccia con aghi da mina, introducendo così nell’alpinismo il controverso concetto di passare comunque e con qualunque mezzo).

Tra il 1879 e il 1880 Mummery e Burgener realizzarono la prima salita della già tentata Cresta di Zmutt sul Cervino e il ripido canalone settentrionale del Leone. Ancora una volta sul Cervino, Mummery con Benedikt Venetz tentò anche l'inviolata cresta di Furggen, deviando solo nell'ultima parte sulla via Normale (cresta dell'Hörnli). L'episodio più significativo riguardante l'etica di Mummery avvenne nel 1880: Mummery e Burgener progettarono di scalare il Dente del Gigante, ancora in attesa di essere salito per la prima volta. La cordata iniziò l'ascensione ma arrestò il tentativo di fronte a una placca di granito troppo liscia per essere superata in arrampicata libera. In quella circostanza Mummery lasciò sul posto una bottiglia contenente un messaggio che diceva: "impossibile con mezzi leali". (Ndr: in effetti quel tratto venne superato due anni dopo dalle guide valdostane Jean-Joseph, Baptiste e Daniel Maquignaz forando la roccia con aghi da mina, introducendo così nell’alpinismo il controverso concetto di passare comunque e con qualunque mezzo).

Aiguille du Grepon

Aiguille du Grepon

Grepòn e Aiguille Verte segnarono la fine della prima fase e furono un vero punto di svolta nella carriera alpinistica di Mummery. Dopo le sue spedizioni sulle vette inesplorate del Caucaso (prima salita al Dyhtau, 5203 m, con la guida Heinrich Zurflüh), ritornò sulle Alpi e sul Monte Bianco. La personalità magnetica di Mummery attirò a sè un talentuoso gruppo di alpinisti; la grande abilità acquisita gli permise infatti di arrampicare con alcuni amici alpinisti inglesi come Geoffrey Hastings, John Normann Collie e William Cecil Slingsby, liberandosi dalla necessità di essere accompagnato dalle guide. Non fu affatto una presa di posizione, anzi Mummery mantenne relazioni amichevoli con Burgener, ma una forma di libertà e indipendenza nella pratica dell'alpinismo. Fu l'inizio del "periodo d'oro" di Mummery, durante il quale realizzò alcune impegnative salite e le prime salite senza guida negli anni 1892, 1893 e 1894, accompagnando gli amici in diverse principali ascensioni delle Alpi. La prima salita del Dent du Requin e quella della Ovest dell'Aiguille du Plan sono alcune di queste. Nel 1893 effettuò la traversata del Cervino con la moglie e diversi altri compagni. Il 1894 fu l'ultimo anno delle sue scalate alpine, con la prima salita senza guide dello Sperone della Brenva sul Monte Bianco.

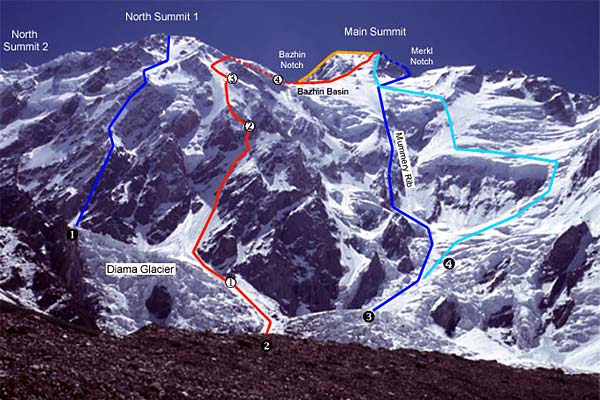

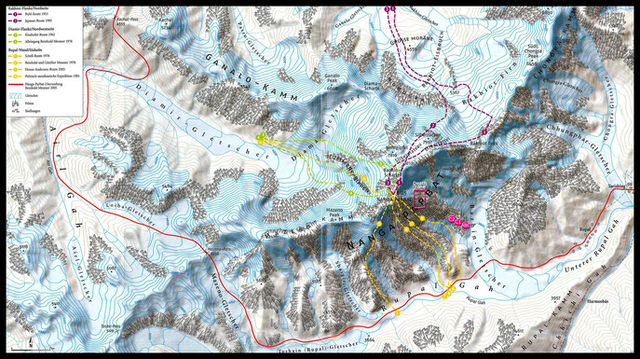

Nel Caucaso Mummery aveva avuto modo di capire il fascino delle terre lontane e delle grandi montagne inesplorate. Così il 20 giugno del 1895 partì per l'Himalaya con l'obiettivo di scalare un Ottomila. La scelta cadde su uno fra più difficili e pericolosi, il Nanga Parbat 8125 m, la nona montagna più alta della terra e la seconda in Pakistan, chiamata "la montagna nuda" per la sua posizione isolata rispetto all'adiacente catena del Karakorum, non lontano in direzione Nord-Est. La sfida, condotta nel modo che diversi anni dopo sarebbe stato chiamato "stile alpino", era enormemente in anticipo rispetto ai tempi (ricordiamo che il primo Ottomila, l'Annapurna, fu conquistato solo nel 1950) e assolutamente sproporzionata non solo in relazione all'attrezzatura, alle conoscenze e alle tecniche di allora ma anche per la scelta di effettuare l'ascensione con una squadra ridotta al minimo. Solo sei uomini per sfidare una montagna gigantesca, di cui all'epoca non si conosceva quasi nulla e con avvicinamento estenuante: Mummery con altri tre alpinisti britannici, John Normann Collie, Geoffrey Hastings e Charles Bruce e i due portatori Gurkhas Raghobir Thapa e Gaman Singh. Dopo l'avvicinamento lungo l'immenso versante Rupal, la squadra attraversò il complesso versante Diamir e raggiunse la quota di quasi 6100 metri lungo quella che ora viene chiamata "Mummery Rib".

Il tentativo si arrestò e mentre Collie, Bruce e Hastings abbandonarono a causa di problemi di mal di montagna, il 24 agosto Mummery fece il periplo della montagna alla ricerca di nuove possibilità, compiendo un ulteriore tentativo solo con i portatori tra le cime secondarie del Nanga Parbat II e del Ganalo Peak, con l'intenzione di ricongiungersi con i compagni sul versante Rakhiot. Purtroppo i tre uomini scomparvero, probabilmente vittime di una valanga nel tentativo di superare il Diama Col per raggiungere il ghiacciaio Rakhiot. Il Nanga Parbat verrà salito lungo questo versante da Hermann Buhl ben cinquantotto anni dopo, mentre il versante Rupal dovrà attendere addirittura settantacinque anni.

Principali ascensioni di Mummery

1879: Cervino, Cresta di Zmutt

1880: Cervino, canalone nord del Colle del Leone

1881: Aiguille Verte dal ghiacciaio Charpoua

1881: Aiguille du Grépon

1882: Aiguille des Grands Charmoz

1890: Dych-Tau (Caucaso)

1892: Aiguille des Grands Charmoz (prima ascensione senza guide)

1893: Dent du Requin

1894: Monte Bianco, sperone della Brenva (prima ascensione senza guide)

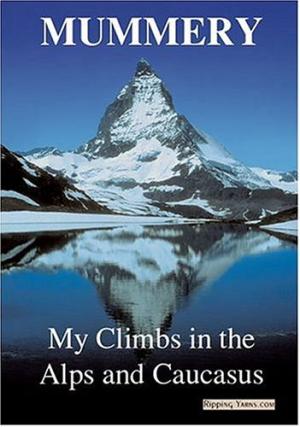

"My Climbs in the Alps and the Caucasus" - Albert Frederick Mummery

"Albert Frederick Mummery" - Spiro Dalla Porta Xidias, Torino, Ed. Nordpress

"Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage: the lonely challenge" - Hermann Buhl

"The naked mountain", Reinhold Messner – Pubblicato in inglese nel 2003. Storia della prima ascensione del versante Rupal del Nanga Parbat nel giugno 1970 e della successiva morte di Gunther Messner durante la discesa sul versante Diamir

"The naked mountain", Reinhold Messner – Pubblicato in inglese nel 2003. Storia della prima ascensione del versante Rupal del Nanga Parbat nel giugno 1970 e della successiva morte di Gunther Messner durante la discesa sul versante Diamir

"Nanga Parbat the killer mountain" - Karl Herrligkoffer

*****************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

Questo articolo è stato tradotto dall’originale in lingua inglese pubblicato da Silvia Mazzani sul sito SUMMITPOST

In February 2016 Nanga Parbat has worldwide taken the lion's share on the front pages of the mountaineering chronicles in reason of the successful first winter ascent by an Italian-Spanish-Pakistani team. Nanga Parbat, after 28 failed attempts, had remained one of the two 8000s, being K2 the second one, never climbed in wintertime. Actually from a latest British study it seems that K2 had already been climbed in winter ascent by a French expedition in the year 1979 (Montagna TV). This article deals with the outstanding figure of the first man on earth that even in the year 1895, over a century ago, attempted the first ascent of this majestic mountain by an extraordinary light-weight endeavour. A concept must be clear before start talking about Albert Frederick Mummery (10 September 1855, Dover, UK - 24 August 1895, Nanga Parbat, Pakistan): as widely emphasized he was a veritable forerunner of modern mountaineering, in fact his views about climb were absolutely in advance if compared to his time, the late Nineteenth, and his cutting-edge climbing concepts really anticipated the Twentieth century. He is reputed as “the father of modern Mountaineering". He was innovative not only for being one of the first mountaineers to break with the tradition of guided climbing and to show its feasibility in practice, for example in the year 1894 on the Brenva Spur, but also a striking forerunner in expanding his horizons and engaging himself absolutely ahead of its time: he considered the highest mountains on earth as a possible new and ambitious goal.

Mostly known as the first man in history who planned and attempted to climb a 8000s, actually was one of the greatest mountaineers of all time: previously he had realized many varied challenging climbs on the Alps and also carried out a couple of expeditions in the Caucasus, in 1888 and in 1890, during which he summited Dykh-Tau 5198 m. Mummery is also remembered for his ethics, staunch supporter of the great value of a honest confrontation between man and mountain: he was among the first ones to support the need of climbing without artificial means, only counting on what he himself called "fair means”. He wrote "the art of mountaineering is to improve the talent at the height of peaks by fair means".

After the death of father, Albert and his brother William were sent to the Alps for a holiday. There, as Albert later wrote in his famous book "My Climbs in the Alps and the Caucasus", "the crags of Via Mala and the snows of the Theodule raised a passion within me, which has grown with my years, and has to no small extent moulded my life and thought." His first ascent on the Alps dates back to 1871, when he climbed Matterhorn, just at fifteen. The first phase of his activities (1879-1890) took place with the great Swiss alpine guide Alexander Burgener (1845–1910), author of the first ascent of many peaks and new routes in the Western Alps. Together with Mummery, he made the first ascent of the Zmuttgrat on Matterhorn on 1879, Grands Charmoz and Aiguille du Grépon (1881). With another British alpinist, Clinton Thomas Dent, he made the first ascent of the Lenzspitze and the Grand Dru. He was killed by an avalanche on 8 July 1910, near the Berglihütte in the Bernese Alps.

Mummery and Burgener formed a strong team, realizing different challenging ascents on the Alps, but Mummery was innovative also in this and from 1892 onwards he was one of the first mountaineers to climb without a guide. At the end of the Nineteenth century the stunning granite peaks of Aiguilles de Chamonix, although representing an irresistible appeal, had not yet been taken into account by the climbers of that era, as deemed extremely difficult. Mummery and Burgener conceived to climb, and succeeded, some of these “impossible needles”: Aiguille des Grands Charmoz (with Benedikt Venetz), Aiguille Verte along the Charpoua side (without crampons) and a few days later the inviolate and stunning Grépon 3482 m, the alpine climb which made Mummery most famous in reason of its boldness and its difficulty, considered as the greatest rock climbing realized until then. Mummery celebrated with a bottle of champagne on the summit and also this significant particular reveals his personality and his propensity to cut ties with the previous dramatic conception of mountaineering. Mummery repeated this latter climb in 1893, without guides. Between 1879 and 1880 Mummery and Burgener realized the first ascent of the unattempted Zmuttgrat on Matterhorn and the steep Northern Lion gully. Again on Matterhorn Mummery also attempted the unclimbed Furggen Ridge with Benedikt Venetz, diverting only in the last part on normal route (Hörnli ridge). The most significant episode about Mummery’s ethics happened in 1880: Mummery and Burgener planned to climb Deant du Gèant, another remarkable and stunning spire, still waiting to be climbed for the first time. They started the ascent, but they stopped their attempt in front of a granite slab, too smooth to be won in free climbing; on that circumstance Mummery left in place a bottle containing a message which said: “impossible by fair means”.

Grepòn and Aiguille Verte marked the end of the first stage and a real turning point in Mummery mountaineering career. After his expeditions on Caucasus unexplored peaks (first ascent to Dyhtau, 5203 m, with the guide Heinrich Zurflüh), he returned to the Alps and Monte Bianco. Mummery’s magnetic personality attracted about him a talented group of climbers; the great skill acquired allowed him to climb with some English friends mountaineers as Geoffrey Hastings, John Normann Collie and William Cecil Slingsby, freeing themselves from the need to be roped in with the guides. It was not a position, rather he maintained friendly relations with Burgener, but a form of freedom and independence in mountaineering practice. It was the beginning of Mummery’s “golden period”, during which he realized some challenging climbs and first ascents without guides in the years 1892, 1893 and 1894, leading his friends on several main routes of the Alps. The first ascent of Dent du Requin and Aiguille du Plan West wall are some of these latter. In 1893 he succeeded in Matterhorn crossing with his wife and several friends. 1894 is the last year of his alpine climbs, with the first ascent without guides of Brenva Spur on Monte Bianco.

In the Caucasus Mummery had understood the fascination of distant lands and great unexplored mountains. So on 1895, june 20th he decided to leave to the Himalayas, with the aim to climb a 8000er. The choice falls on one of the most difficult and dangerous, Nanga Parbat (8125 m), the ninth highest mountain on earth and the second one in Pakistan, called “the naked mountain” in reason of its secluded position from the adjacent chain of Karakorum, not far to the North-East. The challenge, carried out in a way which several years later would be called “alpine style”, was far too much ahead of its time (the first Eight thousander, Annapurna, was conquered only in the year 1950) and absolutely disproportionate both for the gear, the acknowledge and the techniques of the time, both for the choice of climbing with a team reduced to a minimum. Only six men to challenge a gigantic mountain, which at the time you knew less than nothing of, with extenuating approaches: Mummery with three other British mountaineers, John Normann Collie, Geoffrey Hastings and Charles Bruce and two porters Gurkhas Raghobir Thapa and Gaman Singh. After having approached along the immense Rupal side, the team crossed towards the complex Diamir side and reached the altitude of almost 6100 meters (20,000 ft) along what is now called "Mummery Rib". He gave up and while Collie, Bruce and Hastings abandoned for signs of high altitude sickness, on August 24th Mummery walked around the mountain looking for new possibilities, doing a further attempt only with the porters between the secondary peaks of Nanga Parbat II and Ganalo Peak, with the intention of then rejoin companions on Rakhiot side, but the three men disappeared, probably victim of an avalanche in an effort to overcome the Diama Col and move to the Rakhiot glacier. Nanga Parbat will be climbed from that side only fifty-eight years later, while the Rupal Face even will wait seventy-five years.